Ancient Greece as a Key Reference – Not Only for the West

The West's Emergence as a Historical Civilization (Excerpts from "We and the West" – 3/11)

What is “the West”? And how do we relate to it? Over the coming weeks, I will be pre-publishing excerpts from my book Wir und der Westen (und die Welt), ahead of the full English edition’s release under the title We and the West (and the World) later this year. The full list of excerpts is at the end of this post.

Ancient Greece emerged in a world of older civilizations in what is often termed the “Near” or “Middle East” – or, more accurately, West Asia. While it is true that the former terms reflect a West-centred perspective, as a previous post discussed, even the term “Asia” cannot quite escape the omnipresent West as a civilizational-cum-geopolitical reference. In the region between Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean, the Sumerians, Babylonians, ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians, and Canaanites, among others, had developed civilizations of higher complexity. During the Classical period (ca. 480–336 BC) and the so-called Hellenistic period (ca. 336–27 BC, beginning with Alexander the Great), ancient Greece itself coalesced into a politically powerful entity that shaped many developments that would prove profoundly influential for subsequent world history. Important examples of this Greek influence include political ideas, literary, artistic, and architectural developments, as well as achievements in philosophy and science in general. Indeed, many of today’s words and concepts, along with the ideas associated with them, trace their origins back to the ancient Greeks.

Ancient Greece is typically invoked as the first major reference point for the West. It is considered nothing less than the cradle of Western civilization. Indeed, the later West bears influences of ancient Greece and has consciously and actively referred to it at certain times. But how direct is the line from the ancient Greeks to the modern West? Is it permissible to conclude that Greece founded the West – and only the West – and that the West can therefore claim Greece for itself and only for itself?

As we shall see, the construction of the modern West required, in addition to the ancient Greeks, at least the essential building blocks of Romanization, Germanization, and Christianization, which can only be partially placed in a direct line with the Greeks. Perhaps even more important, however, is the fact that Greek influence was not confined to the West but extended beyond the Mediterranean and West Asia, reaching as far as India. An exclusive claim therefore seems unjustified, as other traditions also see themselves as successors to the Greeks or have at least been influenced by them. As mentioned earlier, the Arabs drew upon Greek philosophy and science and even enabled their preservation and transmission during the European Middle Ages.

The extent of ancient Greece’s impact on the later West is undoubtedly considerable. The most important contemporary political concept, “democracy”, dates back to ancient Athens. It is a term that modern global debates cannot circumvent. Democracy (Gr. δημοκρατία, dēmokratía), meaning “rule by the people”, was a groundbreaking concept because it located the origin of legitimate power in the demos, the people. This stood in contrast to oligarchic (rule by a few), aristocratic (rule by a – hereditary – elite), or monarchic (rule by a single individual) systems – terms which also originate from Greek.

The extent to which the concept of democracy has really found its way into political reality is a matter of controversial debate, however. It is also a matter that strikes – as we will have to see in later sections in detail – in the heart of the Western political self-image and its self-ascribed role in the world. Democratic organisational principles certainly do exist and are implemented to some extent in various places. But not only is their implementation incomplete, they also compete with other – more hierarchical and elitist – organisational principles. At the very least, even if it remains incomplete as a reality, democracy as a concept and an idea is omnipresent and unavoidable.

The very idea of granting political participation to segments of the population allows for increasingly inclusive interpretations of power. Although the Athenian demos was restrictively defined (in principle, including only men with two Athenian-born parents), the core concept contains the seed to include other categories of people. In this way, the Greek idea of democracy can be seen as a precursor to the later principle of popular sovereignty, which holds that power is not only exercised by the people but is also rooted in the people, who are sovereign and must be regarded as such.

In the realm of art and culture, Greek influence is equally profound. Architectural monuments like the Athenian Acropolis have inspired countless later structures. Classical Greek sculpture is an indispensable pillar of art history. Furthermore, the emergence of Greek drama, through the works of playwrights like Sophocles, Aeschylus, Euripides, and Aristophanes, holds a central place in the history of literature.

Philosophy presents another case where both the term for the thing and the thing itself are commonly traced back to ancient Greece. While the term undoubtedly originates there, the widespread attribution of philosophy’s very origins as a thinking practice to the Greeks demands scrutiny.

If one defines philosophy as a set of specific intellectual practices – such as the sustained inquiry into metaphysics (the fundamental nature of being and reality), epistemology (the theory and limits of knowledge), and the formal principles of logic – then there is indeed a case that the Greeks were the first articulate and systematic developers at least of certain aspects.

However, if we define philosophy more broadly as the systematic, rational inquiry into all fundamental questions of human existence, then confining its origins to Greece does not do justice to the importance of other intellectual traditions. Foundational contributions to ethics, political thought, and aesthetics emerged independently and robustly in, for instance, the Chinese and Indian traditions.

On what grounds, then, is it warranted to claim that a specific tradition and the questions it asked are more important than those of another one? Is there not a significant risk that unexamined assumptions within a tradition might not only enable inquiry in certain directions and certain ways but also limit it in other? Furthermore, who is in a position to ensure that no biases related to a civilization’s geopolitical dominance cloud our judgment?

The importance of the Greek philosophers is in no way to be downplayed here. Plato and Aristotle, or the Socratic method, account for groundbreaking contributions. However, a degree of caution against hasty conclusions seems to me to be warranted.

To illustrate this, let us return to the previously cited History of Philosophy by the German philosopher and author Richard David Precht. He proactively concedes that other traditions have produced important insights, though he lacks – due to linguistic and civilizational knowledge – direct access to them. But is it in this case still justified to call his book series a “History of Philosophy“? Would it not be more accurate to title it a “History of Western Philosophy”? What is the implicit claim that Western philosophy is philosophy based on? Would the author say the title is merely a rhetorical device, and what he really means is not philosophy, but Western philosophy?

Alongside this substantively important question, there is the question of terminology. Should one retain the term “philosophy” as an umbrella term for all systematic thinking of all traditions, thus making “Chinese philosophy” a valid category? Or should the term be reserved for the Greek tradition and the traditions building on it, such as the Western one, and would it therefore be better to speak of “Chinese thought”? This latter approach remains, however, compatible with unwarranted implicit evaluative claims defining one tradition of thinking – in this case “Greek philosophy” – as the one “true” form of systematic thinking, thereby raising the question of whether it is legitimate to deny that status to other intellectual traditions.

The universalist claim of real, existing philosophy suggests an aspiration for the first option – the pursuit of universal truths. But do the results of this same real, existing philosophy actually inspire confidence that its practitioners are engaging in universalist thinking, and not in a mode of thought that is firmly rooted in one tradition, and thus inevitably comes with its own specific reach as well as its own specific limitations?

There is indeed the opposite risk of abandoning the pursuit of universal thought without good reason. One could place all traditions on an equal footing, refraining from any evaluative judgment of their intellectual – as well as moral, and other – contributions. That would be a form of relativism, and is potentially the opposite pole on the spectrum of intellectual dishonesty, on the other side of self-centered arrogance.

Ultimately, everything hinges on what philosophy is, what it ought to be, and what it can be. These are, themselves, quintessentially philosophical questions. Is philosophy, in practice, capable of breaking out of its own tradition and overcoming it? Is this even desirable, and is it possible? If it proves impossible in practice, could it become possible with growing knowledge and understanding? And who is ultimately qualified to make such a judgment, if not through a deep understanding of at least two distinct intellectual traditions? Precht admits he lacks this capability. But how much curiosity should we expect from someone in his position to actually pursue this essential question?

A compelling example for comparing intellectual traditions comes from Julian Baggini’s 2018 book How the World Thinks: A Global History of Philosophy. In one chapter, Baggini outlines how Western, Indian, and Chinese traditions have conceptualized the “self.” He identifies a focus on the atomistic self in the West, on the relational self in China, and on a “no self” in India.

It is a fairly well-known idea that the West is characterized by individualism and that this is at least partly attributable to Greek philosophy. Baggini points out that this indeed appears to be the case. More importantly, however, he suggests that this particular focus within the Western tradition may have caused it to neglect or under-explore other fundamental questions.

On a different level, philosophy is an interesting example for illustrating the West’s influence in the world. East Asia once more provides an illuminating context for this examination. The contemporary Japanese term for philosophy, tetsugaku (哲学), dates back to the 19th century, when Japanese scholars, in the context of Western expansionism, began to engage more intensively with Western thought. The core issue in the background was the question of how to confront the West and, in light of this, how to deal with one’s own tradition.

Among the scholars arguing for the necessity of a deep engagement was Nishi Amane (西周, family name Nishi, 1829–1897). In his work, he coined the word tetsugaku, attempting to approximate the Greek original with a Sino-Japanese neologism (classical Chinese serving a somewhat analogous role to ancient Greek in a Western context) of similar meaning. The character tetsu (哲) conveys the meaning “wisdom”, akin to the Greek sophia (σοφία), while gaku (学) means “learning” or “study”.

The word tetsugaku thus roughly translates to “the studied pursuit of wisdom”, which comes close to the Greek φιλοσοφία (philosophia, “love of wisdom”).

As an anecdote – a thought that I do not recall having seen formulated anywhere, but I suspect it is not new – it seems worth mentioning that a literal back-translation of tetsugaku actually more closely matches the Greek word philology (from logos, λόγος, meaning “word,” “reason,” or “rational argument”). My hunch is that such a word creation would have worked less well in a Japanese context, which is likely why Nishi decided as he did.

But the meaning of the word is more important than the word itself. As we have seen, the debate continues today: should “philosophy” refer to all deep, systematic thinking in the world, or just to the tradition that started in ancient Greece and developed further in the West? Nishi Amane, the man who coined the term tetsugaku, made this same distinction between Western “philosophy” and Eastern “thought.” For him, the point was to found this field of study in Japan, so that Japanese thinkers could also make philosophical contributions.

It is also interesting to note that this Japanese neologism was later adopted into Chinese during the 19th century. As a word consisting of two Chinese characters, there were no linguistic difficulties in integrating the Japanese word into Chinese. Pronounced tetsugaku in Japanese and zhéxué [approximately “jreh-shweh”] in Chinese, it became the standard term for philosophy in China as well. Naturally, the conceptual and substantial debate over philosophy’s scope is equally relevant there – a topic I hope to explore in greater detail at a later time.

Beyond politics, culture, and philosophy, Greek influence extends to science in a broader sense. Foundational discoveries in mathematics and physics are particularly noteworthy. To this day indeed, letters from the Greek alphabet are used as standard symbols for mathematical and physical quantities around the globe.

Furthermore, Western historiography draws upon Greek “historians” like the previously mentioned Herodotus or Thucydides. The latter is particularly prominent today in discussions surrounding the so-called “Thucydides trap.” Thucydides wrote about the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta and observed that the conflict between the rising power of Athens and the established power of Sparta was likely inevitable. According to the theory of the Thucydides trap, the decline – respectively the rise – of a great power invariably leads to a military confrontation with the rising – respectively declining – other great power. In today’s geopolitical context, the debate centers on the extent to which China’s economic and military rise will lead to a strategic rivalry with the established previously hegemonic superpower, the United States, and how to address this.

I would like to offer one final example of the West’s global reach via the Greek language: the word monochrome. In English, it means “single-colored”, deriving from the Greek μόνος (mónos, single or one) and χρώμα (chrōma, color). As is often the case, this Greek-derived word exists in nearly identical forms in other European languages like French and German.

Through English, the word has even made it into standard Japanese. It exists in the long form monokuro–mu (モノクローム), though the abbreviated monokuro (モノクロ) is more common.

This raises a fascinating question: how much more distant is the word monochrome for a Japanese speaker than for a native English or German speaker? It’s hard to gauge how many people in any Western country truly understand the word’s Greek roots. Westerners might know the etymology, or they may have simply memorized the word.

Even for them, Greek is a distant, classical language. But at least its components as recurring fragments within their own linguistic and civilizational fabric are an omnipresent phenomenon. Now, imagine what it would take for a Japanese person to grasp the word’s meaning intuitively without resorting to pure memorization. How much further is the cognitive distance?

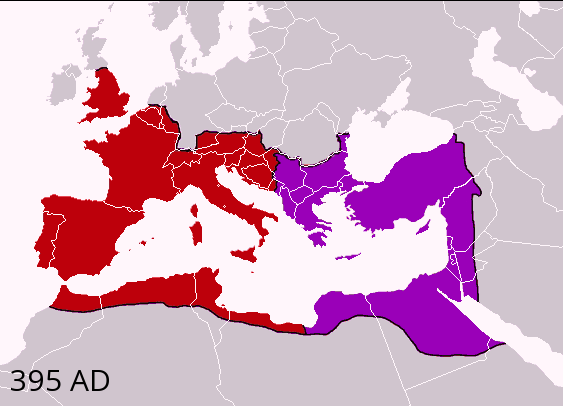

Illustration: Latin and Greek administrative language zones in the Roman Empire

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_world

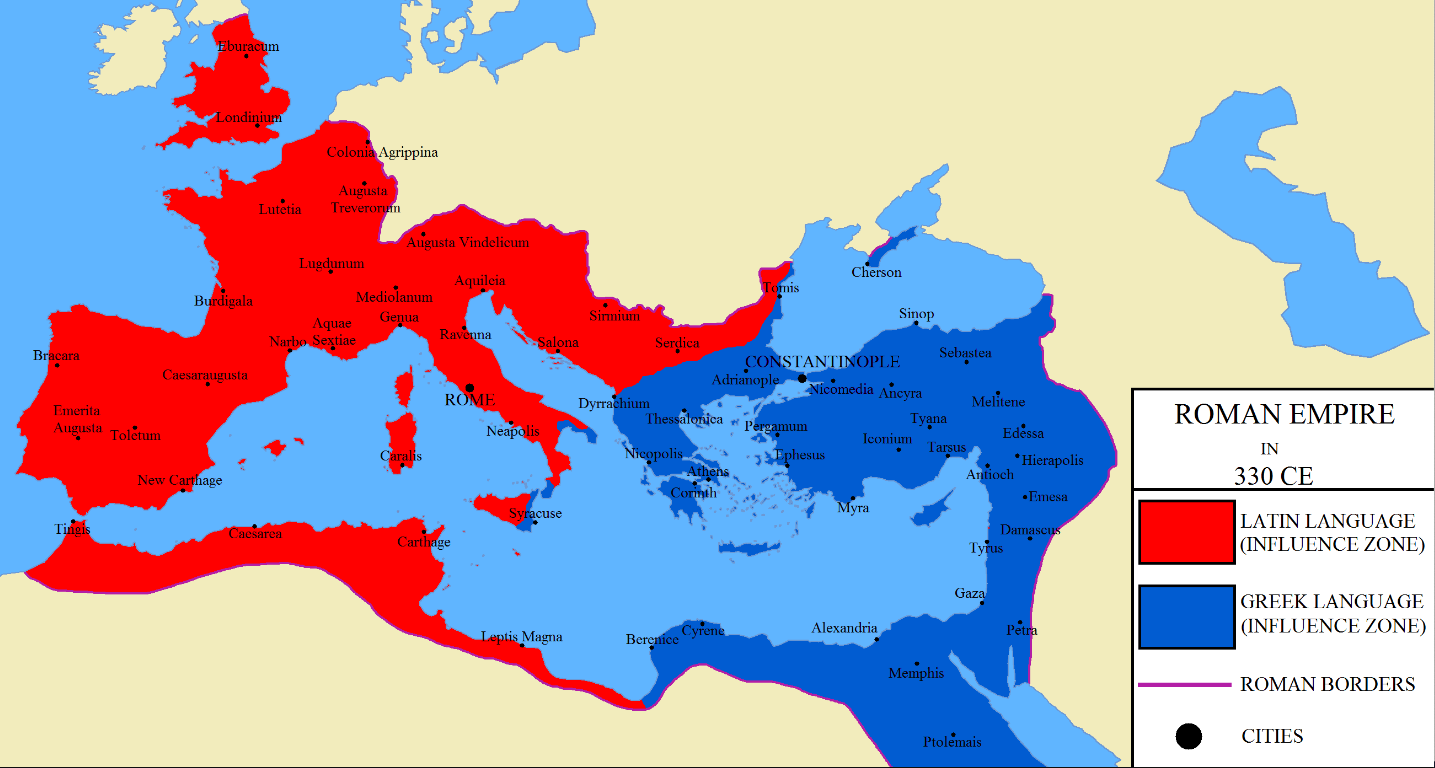

In the final centuries before the common era, ancient Greece was incorporated into the Roman Empire, shifting the political center of gravity to Rome. Yet, Greece’s civilizational influence, particularly its linguistic legacy, endured. For centuries, Greek remained the official language of the eastern half of the Roman Empire.

Following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, Eastern Rome with its capital Constantinople became the center of the continuing Roman Empire for another full millennium. This discontinuity is part of what complicates any attempt at drawing a direct and unbroken line of succession from ancient Greece to the modern West.

Illustration: Zones of Latin and Greek linguistic influence in the Roman Empire, 330 AD

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_East_and_Latin_West#/media/File:

Roman_Empire_330_CE.png

[This chapter concludes the excerpts from the book We and the West’s historical section “The West’s Emergence as a Historical Civilization”. The book also contains chapters on “The Roman Empire – Starting Point of the West?”, “Germanization after the Fall of the Western Roman Empire”, and “Christianization”.]

PRE-PUBLISHING HERE OVER THE COMING WEEKS

Excerpts from We and the West (and the World):

I. The West’s Emergence as a Historical Civilization

→ 1/11 The “West” Merely Relative? – Geographically Western Eurasia

→ 2/11 First Traces of the West 2500 Years Ago?

→ 3/11 Ancient Greece as a Key Reference – Not Only for the West

II. The West’s Trajectory toward Modernity

→ 4/11 Switzerland’s Emergence at the Heart of the West

→ 5/11 Western Expansion and Imperial Continuity

→ 6/11 The West in Modernity – The Measure of Almost All Things

III. The West as a Contemporary Entity

→ 7/11 The West in the Global Order

→ 8/11 Unipolar, Hegemonic, Transatlantic Biases

→ 9/11 Various Moral Souls in the West’s Breast

→ 10/11 Western Modes of Functioning – “Liberal” and “Democratic”?

→ 11/11 Barely Veiled Oligarchies? Truly Legitimate Social Order?

→ Bonus: Whither, Post-Unipolar West?