The West in Modernity – The Measure of Almost All Things

The West's Trajectory toward Modernity (Excerpts from "We and the West" – 6/11)

What is “the West”? And how do we relate to it? Over the coming weeks, I will be pre-publishing excerpts from my book Wir und der Westen (und die Welt), ahead of the full English edition’s release under the title We and the West (and the World) later this year. The full list of excerpts is at the end of this post.

While Western actors have projected colonial and imperial force outward for the past five centuries, Western civilization itself has not faced any existential threats from external, non-Western, powers for a long time. What is more, for centuries there have been scarcely any moments when Western political constructs, ideas, and realities have not been the measure of almost all things.

This had not always been the case. First came the early episodes, such as the Greco-Persian Wars (5th century BC) and the Second Punic War with Hannibal’s march on Rome (c. 200 BC), which threatened the civilizational references of the later West – ancient Greece and Rome. In the 5th century AD, a combined Roman and Germanic force defeated Attila the Hun, halting the Hunnic advance into Western Europe. Then came the Arab expansions of the 7th-8th centuries and later the Ottoman expansions of the 16th-17th centuries, which were stopped at Tours and Poitiers in 732 by Charles Martel and at Vienna in 1529 and 1683, among other places. Furthermore, the Mongols, who in the 13th century had conquered nearly all of Eurasia from China to European Russia, defeated a Polish-German army at Legnica in 1241 (in modern-day western Poland) but advanced no further due to internal power struggles. Finally, during the Soviet era, there existed a Russia-centered opposition to the “geopolitical West”, even as Russia itself could largely be considered a European – and in that sense, a Western – power. This historical context makes the recent geopolitical events and current tensions between the West and Russia all the more significant.

Aside from the cases mentioned above, the West as a civilization in the modern era was almost exclusively preoccupied with its own expansion. This privileged position afforded it the luxury of not having to present itself as a unified entity, allowing it to focus instead on West-internal conflicts. This dynamic has become so pronounced that, given the West’s global power, the fundamental question arises whether a shared Western identity on the level of Western people and nations ever truly developed. The question is difficult to answer and could be approached from various angles. Let us first attempt to concisely trace the development toward modernity.

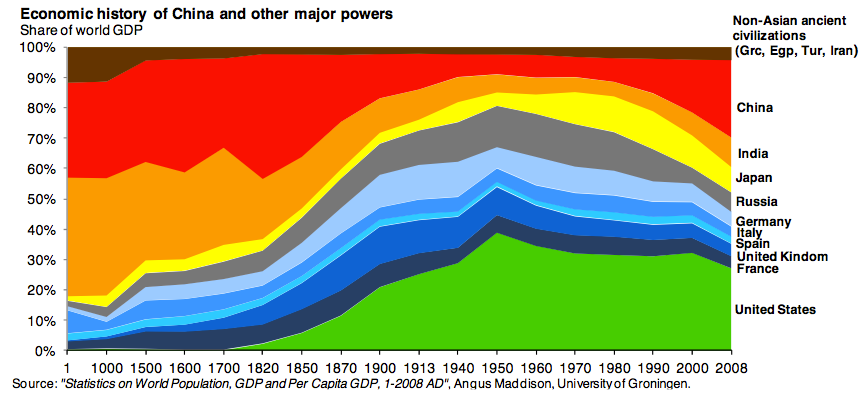

As briefly indicated above, Western supremacy is a historical anomaly. Although Western expansion began around 1500, Europe’s economic development lagged behind that of India and China for centuries thereafter. The West’s two-century-long economic dominance was only cemented by the Industrial Revolution, which relied on imperial tactics like the British dismantling of India’s textile industry. In this light, the shift of the geopolitical center of gravity back to Asia is nothing other than a return – a “re-orient-ation” (in the double meaning of the Orient as the East and orientation as a sense of direction) – toward a previous equilibrium.

As vast and all-encompassing as the West may seem and still be today, this period of dominance is remarkably brief if looked at from a longer historical perspective. Just five hundred years ago, Western Europe represented a fraction of the economic and political importance of the Indian and Chinese civilizations. For many centuries, Asia with its twin giants China and India stood at the center of the world economy. It was only through the combined phenomena of European imperialism and the Industrial Revolution that Western Europeans, and later North Americans, rose to economic prominence, primarily over the course of the 19th century. According to economist Jeffrey Sachs, between 1820 and the end of the Second World War, Asia’s share of global economic output plummeted from about 60% to roughly 20%, while the region’s population remained constant at about 60% of the world’s total.

Illustration: Economic development of world regions over the last 2000 years

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/06/the-economic-history-of-the-last-2-000-years-in-1-little-graph/258676/

Beginning roughly with the founding of the old Swiss Confederacy, developments in Europe started to accelerate, placing pressure on the feudal social order and gradually eroding it. This set in motion a process that continues to this day. Conceptions of how people should relate to one another and what kind of social relations – roles, statuses, and classes – ought to exist developed and clashed. The hierarchical feudal order of manorialism, vassalage, and aristocracy, characterized by personal dependencies, was increasingly met with ideas of a new distribution of power, freedoms for emerging social classes, and soon, the rights of the individual. To this day, and surely for some time to come, it makes sense to interpret societal realities as well as conceptions of them as part of a continuous development originating from this very process.

The previously mentioned upswing in trade, the concomitant rise of cities, and the spread of literacy fostered a growing urban economy that was less dependent on agriculture and feudal manorialism. A new, wealthy social class – that of merchants and traders – emerged and became an economic and political force that opposed the feudal structures. The transition from a barter to a money economy weakened feudal dependencies by allowing peasants to pay their dues in cash rather than in kind. Technological improvements in agriculture contributed to higher productivity, reducing the peasants’ dependence on their lords. Finally, monarchs began to centralize their power, forming stronger, centralized states that undermined the authority of local feudal lords. The establishment of standing armies, paid for and controlled directly by the king, further diminished the military importance of the feudal nobility.

The intellectual currents of the Renaissance and Humanism brought about a rediscovery of the ancient cultures of Greece and Rome, placing a new emphasis on the value of the individual. Renaissance artists increasingly focused on portraying individual characteristics and personalities, for instance in portraiture, where artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer created realistic and detailed depictions that highlighted the character and uniqueness of their subjects.

In literature, individual experiences and emotions were increasingly explored. A prime example is Francesco Petrarca, who wrote personal poems and stories that foregrounded the inner world and personal development of his characters. Humanists like Erasmus of Rotterdam emphasized the importance of a comprehensive education aimed at developing individual potential. This education was intended not merely for acquiring professional skills, but for the moral and intellectual cultivation of the person.

Humanist philosophers also emphasized the importance of human reason and the individual’s capacity for moral choice. They argued that through education and reflection, every person was capable of leading a virtuous life. This stood in stark contrast to the prevailing medieval worldview, which had rather rested on divine predestination.

The Reformation, in turn, led to a fundamental questioning of the Catholic Church’s authority and the formation of new, often less hierarchical, religious communities. Reformers insisted that believers should have direct access to the Holy Scriptures, a principle that profoundly reshaped individual responsibility and personal religious experience. Concurrently, technological changes like the invention of the printing press enabled broader access to knowledge and new ideas, which in turn fostered critical thinking among the general population.

Thus a new understanding of human beings emerged: that of a self-determined, rational individual whose personal striving and self-fulfillment were of central importance. The new emphasis on the individual and on education fostered greater social mobility, as learning and personal merit enabled people to improve their social status. From this soil grew ideas of individual rights and freedoms, which laid the groundwork for later political philosophies and movements such as democracy and civil rights.

All these developments culminated in the major revolutions of the modern era: the intellectual revolutions of modern science and the Enlightenment; the socio-economic Industrial Revolution of the transition to new production processes along with new social classes and movements for social justice and workers’ rights; and the political revolutions that brought about the abolition of monarchies, the establishment of republics and parliaments, and the introduction of civil rights.

In the intellectual field, Kepler, for instance, combined the observation of the planets with theoretical reasoning, thereby applying the scientific method to understand and explain the universe. Kant, for his part, called upon people to emerge from their self-incurred immaturity, to bring together their reasoning capacity with their freedom in the project of “Enlightenment”, and to dare to think and to know.

Industrialization led to the production of new and more easily accessible goods as well as to a working class that began to struggle for rights and better living conditions. In this way, concessions such as shorter workdays, weekends, paid holidays, and social insurance were achieved, eventually expanding into comprehensive systems of social security and efforts to combat discrimination and inequality. Finally, the idea of political equality and freedom, carried by supportive social movements and coalitions, led to the implementation of democratic forms of government and the extension of participation – first to male citizens, and eventually to women.

These are the processes of so-called modernization, that is, the transition from a “traditional” to a “modern” society. It was precisely these novel lifeworlds and worldviews of “modernity” that, around the turn of the 20th century, prompted the creation of a new scientific discipline – sociology – to study them.

In addition to the phenomena already outlined – industrialization (the transition from agrarian to industrial production), rationalization (the growing role of science and technology), the Enlightenment (the idea and practice of human autonomy), individualization (the increasing emphasis on individual rights and freedoms), and democratization – this modernization also entailed two further shifts: increasing urbanization, meaning a growth in urban populations and the importance of anonymous city life; and a broad secularization, meaning a decline in religious influence in both faith and daily life. Integral to all these processes was likely also a general acceleration of life, as well as a fundamental belief in the progressive nature of all these developments.

The classical sociologists of the early 20th century sought to capture these changes in conceptual frameworks and theories. According to Ferdinand Tönnies, this constituted a transition from the traditional, close-knit, and often family-based social bonds of community (Gemeinschaft) to the modern, instrumentally rational, and often contract-based relations of society (Gesellschaft). Émile Durkheim conceptualized a shift from “mechanical solidarity”, based on similarity, in traditional societies, to “organic solidarity”, which is founded on division of labor and mutual interdependence.

Max Weber emphasized the rationalization and disenchantment of the world, a process driven by increasing rationality, efficiency, and bureaucracy, alongside a decline in magical and religious thinking. Later “classics” of the discipline conceptualized trends of increasing specialization and the division of social functions, a decline of traditional bonds and a rise in individual choice and responsibilities, as well as generally “reflexive modernization” wherein modern societies increasingly reflect upon themselves and their implications, and even a “liquidity” of modern lifeworlds and a state of heightened flexibility and uncertainty amid novel risks.

Thus the aforementioned belief in the progressiveness of all these processes has also been accompanied by skepticism and doubt as to whether they truly constituted human and societal advancement. The debate remains open, and has – given technological capabilities like nuclear weapons since the mid-twentieth century – taken on a straightforwardly existential character for humankind.

As complex as this debate already is when confined to the West – as the social sciences have largely done – it becomes vastly more complex when reflecting upon the applicability of the concepts of modernity and modernization to non-Western societies. Those societies that had the requisite leisure for this, meaning those that were not merely colonized and placed under foreign dominion, were able to experience this conundrum firsthand.

As previously touched upon, both China and Japan, for instance, witnessed intense debates in the later 19th century about how to confront the imperial and technologically superior West. The spectrum of positions ranged from the outright rejection of Western influences to various versions of how the ideas and practices of the Western powers could be adopted and integrated into their own societal fabric. A prominent stance was to preserve their own spiritual values while pragmatically adopting Western science and technology. In addition, some also held the radical position of rejecting their own traditions, which they regarded as backward.

To what extent would the adoption of Western technology lead to a different version of the same phenomenon – modernity – and to what extent would the accompanying changes impair traditional values? Seen in this light, the debate seems to me to be, in its core, analogous to the one within the West itself, where modernization has also been accompanied by critique, albeit with the subtle difference that the developments had first occurred within its own societies and could be assumed to have drawn upon a latent potential within its own civilizational foundations.

The underlying question is to what extent the so-called modernity is to be seen as progress and modernization as a universal developmental process for human societies, or whether modernity and modernization must rather be considered, at their core, as Western developments. To the degree that other civilizations adopted such worldviews, did this signify “universal modernization” or rather “Westernization”? Could it even be that, in the relentless pursuit of modernizing progress, age-old values and traditions had become superfluous and unimportant? Or, conversely, could the upheavals and disruptions brought by Western modernization only be successfully confronted – without losing oneself – by relying on one’s own primordial civilizational values and norms?

In other words, it is a question of whether we are, despite all the modernization in large parts of the globe, to speak of a “single, globe-spanning civilization” in the singular, or still of “multiple civilizations” in the plural. Westerners who have been socialized in the unipolar moment have tended to comport themselves as civilizational universalists and unipolarists. Since technological as well as moral-political development was considered progress-oriented and unidirectional, it seemed permissible or even imperative to many to measure other civilizations against their own standards – standards which were conceived as universal.

During the 1990s and 2000s, it may actually have been difficult to escape this belief entirely. Perhaps it was even a venture worth attempting. But whether a failed, well-intentioned endeavor or an untenable project launched from the outset in arrogant ignorance – the universalizing attempts emanating from the West have shot their bolt and largely failed. The majority of the world population no longer seems to believe that the West represents universal progress. Consequently, the West is increasingly thrown back upon itself. It is grappling with the collapse of its universalist mission and with the necessity of positioning itself as one civilization among many within a multipolar global order.

To what extent do civilizations resemble one another as comparable societies, and to what extent do they differ as distinct and unique traditions? Both perspectives find convincing arguments: a comparative approach with an emphasis on the similar finds an abundance of commonalities and parallels, while an approach focusing on differences finds just as much that is diverse and distinct.

Faced with all the complexity that this generates, one might be tempted to consider orientation impossible or unrealistic. One might be tempted to focus merely on small thematic fields and subordinate aspects, leaving the larger questions aside. I myself, however, do not think we should abandon the attempt to make sense of things with grand theories, for otherwise we will forfeit all coherence and direction. We must only be clear about what we are talking about. To what extent is something the same or different; what exactly, and how? What is “modern” precisely, and for what purpose is the term being used?

All this certainly also holds true for the West. One cannot avoid taking a closer look at the West as a contemporary entity.

PRE-PUBLISHING HERE OVER THE COMING WEEKS

Excerpts from We and the West (and the World):

I. The West’s Emergence as a Historical Civilization

→ 1/11 The “West” Merely Relative? – Geographically Western Eurasia

→ 2/11 First Traces of the West 2500 Years Ago?

→ 3/11 Ancient Greece as a Key Reference – Not Only for the West

II. The West’s Trajectory toward Modernity

→ 4/11 Switzerland’s Emergence at the Heart of the West

→ 5/11 Western Expansion and Imperial Continuity

→ 6/11 The West in Modernity – The Measure of Almost All Things

III. The West as a Contemporary Entity

→ 7/11 The West in the Global Order

→ 8/11 Unipolar, Hegemonic, Transatlantic Biases

→ 9/11 Various Moral Souls in the West’s Breast

→ 10/11 Western Modes of Functioning – “Liberal” and “Democratic”?

→ 11/11 Barely Veiled Oligarchies? Truly Legitimate Social Order?

→ Bonus: Whither, Post-Unipolar West?